- Edgevanta Weekly

- Posts

- Watch the Costs

Watch the Costs

Your essential guide to dominating the civil construction world with the latest tech, market trends, and wisdom.

In 1875, Andrew Carnegie's competitors couldn't understand how he kept undercutting them.

They were profitable. They had good equipment. They knew the steel business.

But Carnegie was eating their lunch. Again and again.

The difference? While his competitors watched profits, Carnegie watched costs. Every day. Every penny.

"Watch the costs and the profits will take care of themselves."

That single idea built the largest steel empire in the world.

Photo Credit: Reve

The System Nobody Else Had

Carnegie developed something revolutionary for his time: a system to track costs day by day, penny by penny. His competition would eye profits. Carnegie would eye costs.

Data on costs and volume were wired to him in New York daily. From there he badgered his managers and tried to inspire competition among his workers. When one plant would triumphantly announce they broke all records that week, Carnegie's response was always the same: "What about next week?"

He tracked the cost of every nail used in his factories. Not because he was cheap. Because he understood something fundamental: when you know your true costs, you can price aggressively, capture market share, and still make money. And you’re doing right by your people’s future by paying attention. Because if you don’t, your competitor will.

By 1896, Carnegie drove the price of steel rails from $28 per ton to $18. Sometimes as low as $14 to capture orders. His competitors were astonished. They couldn't figure out how he was doing it.

The answer was simple: they didn't know their own costs. Carnegie did.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

"We Could Not Afford to Employ a Chemist"

Here's my favorite Carnegie story.

Carnegie was the first steel producer to hire chemists at his blast furnaces. The chemists found the optimal mix of ore, coke, and lime to make pig iron. His competitors thought it was an extravagant waste of money.

Carnegie wrote in his autobiography:

"What fools we had been! But then there was this consolation: we were not as great fools as our competitors. It was years after we had taken chemistry to guide us that it was said by the proprietors of some other furnaces that they could not afford to employ a chemist. Had they known the truth then, they would have known that they could not afford to be without one."

That investment in knowing his costs precisely gave Carnegie what he called "almost the entire monopoly of scientific management."

His competitors were guessing. Carnegie was measuring.

The Compounding Effect

Here's what most people miss about cost discipline: it compounds.

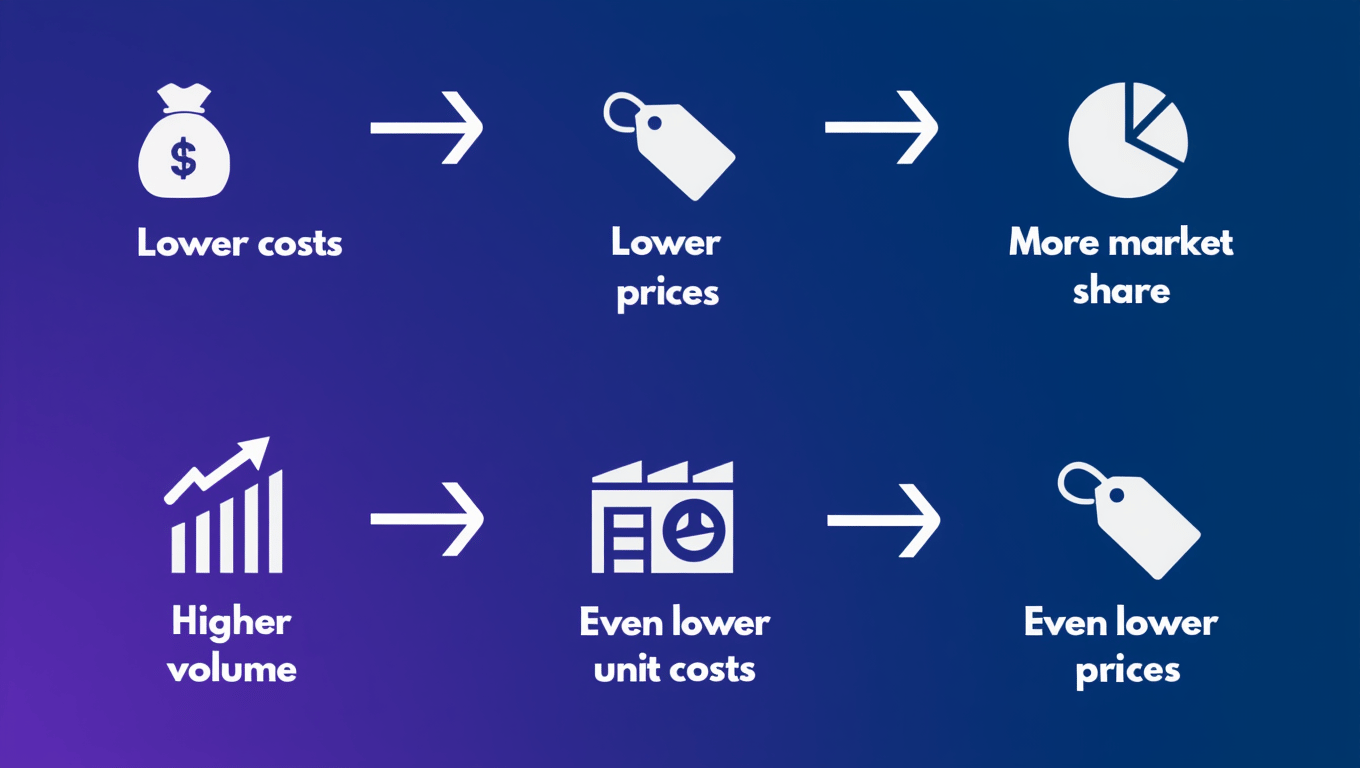

Lower costs → Lower prices → More market share → Higher volume → Even lower unit costs → Even lower prices

By 1900, Carnegie was producing more steel than the entire steel industry of Great Britain. He sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan in 1901 for $480 million. That's roughly $18 billion in today's dollars.

All because he watched the costs.

The power of compounding

Costs Are Permanent

I got this idea from David Senra's Founders podcast episode on Carnegie (Episode #283 - highly recommend). The insight that stuck with me: costs matter all the time. Not just when times are bad.

I've seen this firsthand.

One of our paving divisions was a golden goose. They captured outsized returns for years by being the low-cost producer. Then something shifted. They began to act invincible.

Until they weren't.

Competitors moved in. The market contracted. And we'd gotten soft. Work quality slipped. Housekeeping got bad. "That's not my job" started creeping in. Politics. BS. All that profit had gone to our heads.

We had to nearly rebuild the division. We righted the ship, but we lost some people we never should have had to let go - because leadership took their foot off the gas when times were good.

As Nick Saban says: "Discipline is doing what you're supposed to do, when you're supposed to do it, the way it's supposed to get done - even when you don't want to do it."

Don't think because you're in a good market that you're better than someone who's in a tight one. It's discipline that matters and pays over time. Not whether you won the geographical lottery.

Your competitors who stay disciplined during good times? They're building compounding advantages. When the market turns - and it always turns - they're positioned to survive and thrive while everyone else scrambles.

Photo Credit: Michigan Paving

What This Means for Construction

Carnegie wasn't just watching costs. He was maniacal about it. Data wired to him daily. Questions fired at managers constantly. Competition between furnaces made visible.

Some people think that level of intensity is overkill. It's not.

I worked for a VP who ran the same system Carnegie did - just with trucks instead of furnaces.

Every morning by 6 AM, our team received a note with questions about the daily cost report. Never accusatory. Always specific:

"If someone charged to a change order code, how are we getting paid for the extra work?"

"How does the job ride?"

"How much longer will James be working in the median?"

"Why did we order 26 trucks when 22 should have covered it?"

He wasn't micromanaging. He was doing what Carnegie did - using cost data to understand what was actually happening on his jobs. The cost reports became his intelligence system.

And here's what I learned: even with the best intentions from field supervision, timesheets are often wrong. Quantities get miscoded. Costs drift to the wrong cost codes. If the inaccuracies aren't fixed today, it's near impossible to fix them later.

Daily updates are the only way.

The System:

Foremen submit timesheets by end of shift - crew hours, equipment hours, quantities, notes

Cost reports hit inboxes by early morning showing budget vs. actual for every item

Someone in leadership reviews and asks questions. Every. Single. Day.

Corrections get made immediately - not next week, not at month end

That's it. Review daily. Ask questions. Fix problems now.

Carnegie pitted furnaces against each other. The winning team got to post a steel broom at the top of their smokestack. What if you posted daily production numbers by crew? Made cost performance visible? Celebrated the crews hitting their targets?

Photo Credit: Reve

The VP I worked for used cost reports to build relationships. He knew more about what was happening across the company than anyone - not because he was in meetings all day, but because he read the numbers every morning and asked good questions.

If you think daily cost review is excessive, ask yourself: would Carnegie think it's excessive? The richest man in America tracked the cost of every nail in his factories.

Your competitors who treat cost review as a monthly exercise? They're the ones who "can't afford a chemist."

The Bottom Line

Carnegie built the largest steel company in the world with a simple principle: watch the costs and the profits will take care of themselves.

That principle is just as relevant today on your job sites as it was in Pittsburgh steel mills 150 years ago.

Review daily. Ask questions. Fix problems now.

Do it when times are good. Do it when times are bad. Do it when you don't want to.

That's discipline. That's how you win.

Thanks for reading this week!

P.S. We're growing and hiring.

20+ customers live, coast to coast. Watching estimators bid smarter using tools we built is incredibly rewarding. We're just getting started.

We're looking for a Founding Customer Success Manager - someone who loves construction and wants to own the function that scales us to 100+ customers. You'll work directly with me and the founding team.

Know someone? $2,500 referral bonus. Job details here.

Sources:

In Case You Missed It:

How would you describe today's newsletter?Leave a rating to help us improve the newsletter. |

Enjoyed this newsletter? Forward it to a friend and have them sign up here!

Tristan Wilson is the CEO and Founder of Edgevanta. We make AI agents for civil estimating. He is a 4th Generation Contractor, construction enthusiast, ultra runner, and bidding nerd. He worked his way up the ladder at Allan Myers in the Mid-Atlantic and his family’s former business Barriere Construction before starting Edgevanta in Nashville, where the company is based. Reach out to him at [email protected]